Come In! Private Art Collections in Galleries

Many households hold treasures whose value is understood only by their owner. What might be precious to a collector may seem like mere clutter to others. But what happens when such a personal collection is placed in a gallery? How are viewers supposed to understand it, and what can they gain from looking at objects someone has gathered over time? Artists Magdalena Kašparová, Šárka Koudelová, and Ondřej Basjuk have been nurturing their collections for years, drawing inspiration from them and occasionally exhibiting them. What occurs when a private collection finds itself in an exhibition space, and how does its meaning change from the home to the gallery? Step into a world where the private becomes public, only to slip back into the shelves and drawers of a home. Discover the challenges of working with collections and how they fit into the context of contemporary art.

Why Exhibit Collections?

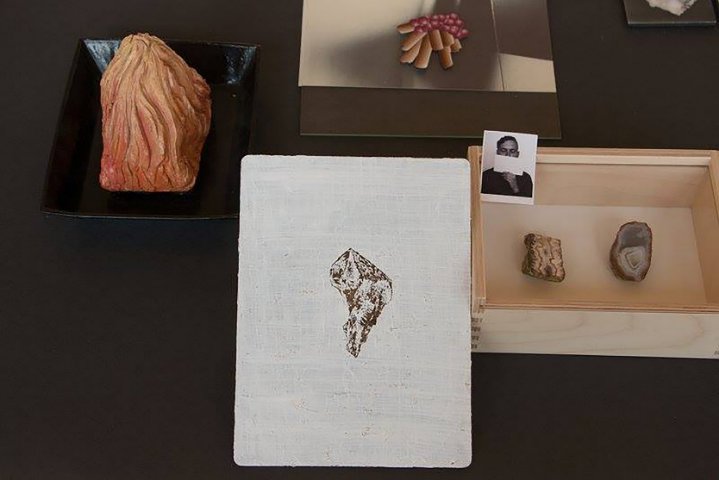

The "Princip ŠAO" exhibition in 2014 directly explored the coexistence of two artist-collectors, Šárka Koudelová and Ondřej Basjuk. In the exhibition text, the pair stated, "Destructive mutual support in founding and maintaining expensive collections combines with a great desire to immediately understand the other’s issue and become the other’s expert / sparring partner." Their collections were displayed on a makeshift table, in boxes, frames, under glass, or simply lying freely. In another part of the gallery space, their paintings were exhibited, where attentive visitors could spot objects from the collections that inspired these works.

The exhibition examined the sharing of interests and themes while preserving individual identity and creativity. This dynamic remains a part of their shared household today, as Ondřej explains: "I think our interests inevitably converge at certain points, like in the form of ‘orientally’ designed Czech porcelain.” Here he alludes to seeing his own interest in Asian art within his wife's porcelain collection. Šárka adds, “I can date Buddhist bronzes, and Ondra shares my interest in stones and jewelry. This shows in art as well; for instance, in my recent exhibition ‘Broken Femur’ (June–August 2024), I referenced the kapala, a Buddhist ritual bowl made from the human skull’s braincase. Ondra had a fairly long period where his paintings were filled with marble monoliths created using painterly effects, and this back-and-forth of inspiration certainly operates at a subconscious level.” The Entrance Gallery exhibition offered visitors a glimpse into this coexistence and sharing, highlighting the collections' role as sources of inspiration.

Magdalena Kašparová views her collections not as mere inspiration but as material for exhibition. At the 4+4 Days in Motion festival in 2020, she presented selections from her 2006–2010 collections in the installation "Personal Archaeology." In the former special education school building in Strašnice, she created a site-specific "room" with small objects displayed on tables and graphic materials framed on walls. The worn-out space formed a striking backdrop, reflecting the artifacts of adolescence in both its everyday and unique forms. Magdalena noted that some visitors had emotional responses to the exhibition: "I was surprised when people told me they were captivated by various pieces of my collection, connecting to them from a sentimental perspective, sometimes recalling their own childhood."

Although Magdalena does not intend for it, her collections stir emotions and evoke nostalgia. "The original intent is genuinely uncalculated, instinctive, and rooted in passion. I just know that I must collect and recognize what belongs in my collection. I often don’t know what will become of a piece or how I’ll use it, but at that moment, I know it must be part of the collection, and then we’ll see."

Šárka uses her collections in exhibitions in an original, conceptual manner. She transfers jewelry's characteristics into other projects she works on. In 2019, this theme was part of an installation for the exhibition "Our Bodies So Soft, Our Lives So Epic" at the Fait Gallery in Brno. “Here, I explored my understanding of jewelry as miniature conceptual objects whose materials and shapes serve as means of communication and store emotions or memories.” Jewelry is closely linked to the human body in this work; palms and soles become pendants, adorned with meticulously crafted decorations. The skin and decorated nails themselves become jewelry.

While Šárka did not directly exhibit her collection here, it indirectly became the installation's theme, with certain objects from her collection making their way into the gallery as part of the artwork. This thinking also features in her project for Designblok, where she is currently collaborating with jewelry designer Eliška Lhotská. “Our collaboration explores how an object, laden with meanings and financial value, withstands time and connects family generations.” The partnership is leading to a conceptual project that examines jewelry from different perspectives. “We also discuss the boundary between functional objects and art, which, in the case of jewelry, I believe doesn’t exist.”

More Views, More Contexts?

Collaborating with others can be highly beneficial when working with collections. It involves allowing someone else to handle objects with strong personal significance or rethinking a collection’s theme to make sense to others. This can sometimes be challenging when the collection has a very personal character. Although Magdalena sometimes collaborates on exhibitions, she insists that she primarily handles her collection herself. “I appreciate help with practical tasks (like cleaning cans, installation...), but the idea must always come from me. Even regarding sorting and arranging... I won’t let anyone else do that.” According to Magdalena, the curator's role is essential for situating collections within a theoretical context or helping communicate the intent to the audience. However, certain decisions remain hers alone. Magdalena adds, “I'm always glad when a curator helps me find the language to explain things if necessary. But I think it often speaks for itself.”

Magdalena worked with curator Milan Mikuláštík on the "Obsessions" exhibition at the House of Art in Zlín during the Contemporary Art Triennial in the fall of 2023. The exhibition's title references the urge to accumulate, organize, and arrange objects—a significant part of working with collections. Magdalena generally takes responsibility for arranging the collection in the exhibition herself, partly because she creates relationships between objects before they are displayed. This process occurs in the privacy of her home.

Living with Objects

Artists constantly work with collections, as they live with them and often engage with them daily. "It’s one of the hardest things about all of this," says Magdalena. "I have to ‘live with things,’ as they continuously surround me and ‘gravitate towards each other,’ magnetically clustering. I often work on collages, whether in time-based media or prints (books, artist prints...), with countless ways to arrange things. This sometimes leads to decision paralysis. But once I get into it, a similar magnetic principle takes over, like with physical objects, where I instinctively know where each belongs."

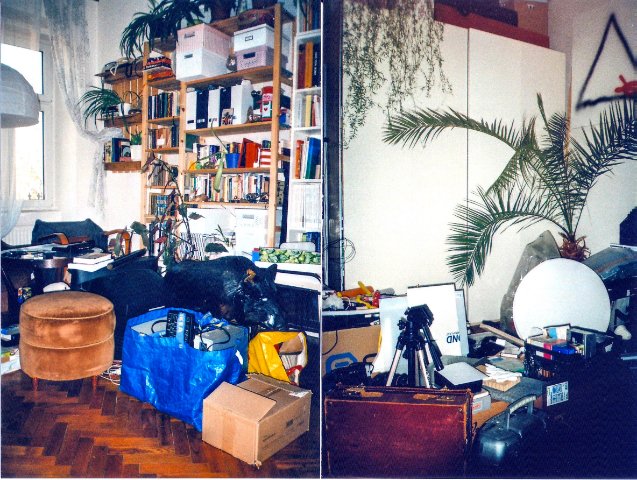

Ondřej’s Buddhist collection has a prominent place in their shared home, where he and Šárka keep their collections. "The sculptures face east. It’s in the best room, one of the two we have," he says, pleased with his arrangement based on a clear key: "The relationship between individual sculptures is iconographic, with the peripheral sections arranged more analogously. This might mean placing objects from different cultures side by side if they share the same century." At the Entrance Gallery exhibition, he spoke about his constant work with these objects, setting them in handmade boxes and engaging with the collection daily. “I don’t do this anymore. I now try to have original boxes and ‘pedestals’ so the collection is authentic from every angle.” Independently, Šárka mentions that their approaches to their collections differ: “Ondra works with his collection daily, continually adjusting, inspecting, and putting things back. We live in close contact with his collection, while mine is generally invisible in everyday life.”

Both are reconciled to life among their collections, and it seems a harmonious coexistence: "I look at layers of green aragonite from Spain from my bed; our son plays with opals from Bohouškovice, and I alternate between wearing and storing jewelry, sometimes leaving them untouched for long periods. Relationships form naturally as we live with these objects." However, collecting significantly impacts their shared life. Ondřej adds, “Sometimes it’s unclear whether the living space belongs to us or the collections. If all is well, it doesn’t matter, but in times of prolonged hardship, like illness, the collection becomes a suspect.”

Private or Public?

The question of exhibiting collections relates to opening personal space to the public. Ondřej, who rarely displays his collections publicly aside from the Entrance exhibition, asked Magdalena: “I’m curious about how you justify your collection to people without an artistic background or an affinity for collecting. My experience is one of continuously defending ‘junk’ that serves no purpose, only collecting dust, and whose further investment is seen as immoral.”

Magdalena replies, “It’s true that justifying it is hard, but fortunately, it’s getting easier since I ‘use it for art.’ It’s a shame, though, because it would be great if people could understand it just as it is. The hardest part was protecting my collections from my mother during my childhood and adolescence. My father, on the other hand, supported my collecting and would bring me items. Generally, it’s a pity that some people fail to see the creative potential, even when nothing tangible is made from these objects. Krištof Kintera (good for him) receives more understanding than someone who simply possesses things and draws inspiration from them.”

According to Šárka, there’s no need to ponder what her collections mean to society. “Collections undoubtedly have significance as they convey a message and possess cultural value. By this, I don’t mean just measurable, socially recognized value. Magdalena’s collections of everyday items, packaging, etc., also form a cultural statement that speaks of her, of humanity, and of impermanence.”

Collections in galleries offer visitors insight into a topic of interest to the artist or a specific stage of their life. They embody both an intimate connection to objects linked to memories and associations and a broader value and memory. In the conclusion of their conversation, Magdalena reflects on the connection between the personal and the public: “I believe this is the essence I’m trying to capture—that ‘the personal can be political,’ political in the sense of universal. I’m not exactly sure how it works, as I mostly work intuitively, but I truly feel that there’s some kind of interconnectedness of all matter that enables identification. For instance, someone sees an object at an exhibition, recalls something from their own life, and begins to think in slightly different contexts. I feel that the more personal something is, the more universal it becomes, which is an interesting paradox I wish someone could explain to me.”